By now, you’ve probably heard a great deal about the Supreme Court’s interim relief docket, also known as the emergency or “shadow” docket – which, although it technically refers to all cases that are not briefed and argued on the merits, is commonly used to describe the cases in which a party comes to the court for an order on an emergency basis without full briefing and oral argument. Currently, much of the discourse surrounding the interim relief docket centers around whether the justices are disproportionately ruling in President Donald Trump’s favor and how often the court is deciding such cases without explaining its reasoning.

I am not just another pundit speculating on the nature of the interim relief docket, and this is not just another article critiquing the justices’ use of it. Rather, I have gathered all emergency applications from the Supreme Court’s 2000-01 term through its 2024-25 term and have been studying these applications for years.

When I analyzed the 2024-25 term, several patterns emerged, which have gotten little attention in academic publications or the mainstream press. Among the most striking is that while overall decisions on emergency applications broke down almost evenly by ideological direction, 75% of the court’s grants of relief had a conservative outcome. And, despite the justices receiving much criticism for their lack of explanations in resolving emergency applications, such explanations have actually increased over time.

A picture of the 2024 interim relief docket

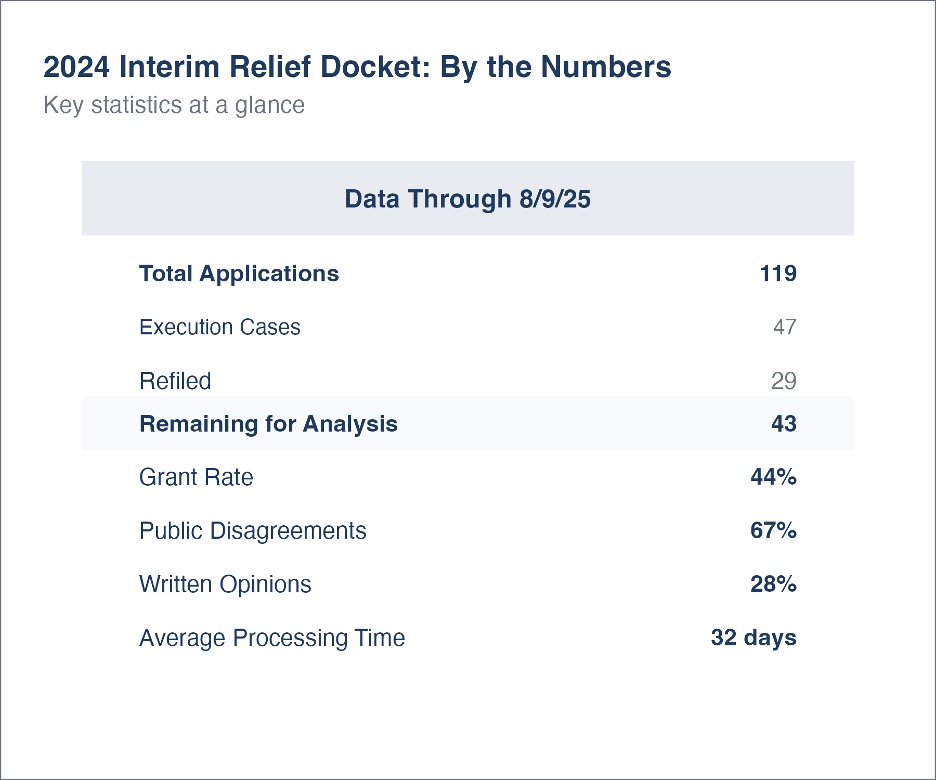

In the period studied, from Oct. 7, 2024, through Aug. 9, 2025, there were 119 emergency applications, which can be broken into three distinct categories. First, there are the death penalty cases. These accounted for 47 (or approximately 39%) of such applications and have traditionally been the most common category of cases on this docket. Specifically, these are requests for the Supreme Court to pause an execution (or allow an execution that is currently paused to go forward). The court has not granted any stays of execution so far this term, as has typically been its practice in the past.

The second category of cases is emergency applications that are refiled. Twenty-nine (or approximately 24% of the) applications fit this category. To understand what these consist of, let’s say an application is filed with Justice Amy Coney Barrett in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit (each justice has jurisdiction over a particular circuit). Barrett denies that application. According to the Supreme Court Rules, the applicant can then refile his or her application with any justice. In our hypothetical, the applicant files with Justice Clarence Thomas in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit. At this juncture, almost all refiled applications follow the same pattern: They are distributed for conference, referred to the full court, and then denied. Since 2000, no refiled emergency applications have ever been granted.

The final category of cases consists of 43 substantive applications involving the core work of emergency relief. In the period studied, these included judicial power cases (challenging courts’ authority to constrain executive action), administrative state disputes (like EPA regulatory enforcement), First Amendment conflicts, and federalism questions about the conflict between state and federal authority. These substantive applications are our focus today and provide the clearest picture of how the court decides emergency applications beyond the routine denial of death penalty and refiled cases.

What do applicants ask for?

Most applicants coming to the Supreme Court’s interim relief docket, whether in cases concerning the death penalty, refilings, or substantive applications, wanted the same thing in the period studied: for the Supreme Court to hit the pause button. Nearly three-quarters of applications asked the court to stay a lower court order, freezing whatever a judge below told them to do or cease doing. For example, in Noem v. National TPS Alliance, the Department of Homeland Security sought to pause a district court order that barred the Trump administration from ending the protected status of some Venezuelan citizens living in the United States. Others requested more active intervention through injunctions, asking courts to immediately order or stop specific lower court actions, such as blocking the removal of Venezuelan men from immigration custody in A.A.R.P. v. Trump.

Something also stands out in 2024 – four applications asking to “vacate the order,” which is traditionally quite rare. This is different from a stay, which pauses an action. These applications want the lower court’s order wiped off the books entirely. This year, all four such requests came from the Trump administration. In Bessent v. Dellinger, the administration sought to vacate a district court’s temporary order restoring the former head of the Office of Special Counsel, an independent agency charged with protecting whistleblowers, to his prior position. The court held the case in abeyance (postponed deciding it) until the temporary order expired, thus avoiding the question until the case was dismissed as moot – that is, no longer a live controversy. In Department of State v. AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, the administration sought to vacate a district court order requiring it to provide $2 billion in foreign aid payments. The emergency application was denied. In Department of Education v. California, the court granted the administration’s request to vacate a district court order requiring federal grant payments linked to DEI materials. And in Trump v. J.G.G., the court granted the administration’s application to vacate an order blocking removals of immigrants under the Alien Enemies Act. The court ruled that immigrants being held by the federal government must challenge their detentions in Texas, where they were being held, rather than in Washington, D.C.

What stood out

Reviewing the data collected from the period studied revealed several notable patterns. Although much has been written on the interim relief docket, the following trends have gone largely unnoticed.

The court is saying “yes” a great deal more than in years past.

During the period under review, the court granted 44% of the substantive emergency applications. This is nearly double the 23% rate from the 2023-24 term. During Trump’s first presidency (2017-2021), the court granted emergency relief of substantive emergency applications at 46%. During Joe Biden’s presidency (2021-2025), the rate dropped to 31%. So far, during Trump’s second term, the grant rate is even higher at 67%. This supports the general narrative that the court has been consistently more receptive to granting emergency requests from the Trump administration than to similar requests from the Biden administration.

Such grants have disproportionately resulted in conservative outcomes.

Most analyses of the interim relief docket have focused on whether the Supreme Court says “yes” or “no” to the applications. But this misses the bigger picture. Just as scholars analyze the ideological direction of the court’s merits decisions (“in the 2023-24 term, the court issued conservative decisions in X% of cases”), we should examine the ideological direction of emergency applications, as well.

To do so, I used the ideological coding scheme for merit docket scholarship used by the Supreme Court Database. For example, in death penalty cases, a “liberal outcome” means the execution is blocked; in judicial power cases, a “conservative outcome” favors limiting courts’ review of an executive action; in economic activity cases, a “conservative outcome” typically favors business interests over regulatory enforcement.

Turning to the data, when we look at the 43 substantive applications in the period studied, the Supreme Court decisions on emergency applications (including grants and denials of relief) broke down almost evenly by ideological direction – 51% liberal, 49% conservative. But when the court chose to grant relief, 74% of those grants on substantive applications produced conservative outcomes. This pattern is not new: Since 2016, roughly three-quarters of the granted emergency applications have produced conservative outcomes across different presidential administrations. Put simply, the interim relief docket appears balanced until you examine the direction in which the Supreme Court grants relief to applicants.

The justices are publicly disagreeing more than ever.

Unlike in cases on the merits docket, we generally cannot see how the individual justices are voting on emergency applications, since the court typically issues only a brief order. Given this, public statements are our only window into how the justices view these decisions. In 67% of the substantive emergency applications from the period reviewed, at least one justice publicly disagreed with the majority, far exceeding historical numbers: Up until 2014, justices publicly disagreed on emergency cases in fewer than three cases per year (averaging 13.5%), with many years containing no disagreements at all. Even after disagreements became more common starting in 2014, they hovered around 30%.

Such disagreements come in two forms: disagreement statements and dissents. Whereas disagreement statements reveal a justice’s voting preference (“Justice Gorsuch would have denied the application”), dissents indicate a justice’s formal opposition (“Justice Kagan dissents”).

Thomas led the conservative dissenters, with 13 total public statements (11 disagreements, two dissents), often going solo (eight times). On the liberal side, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson led with 16 statements (five disagreements, 11 dissents). The liberal justices (Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Jackson) frequently dissented together (appearing as a coalition seven times), while conservative justices more often disagreed individually. The scorecard below provides more details of the justices’ public statements on the interim relief docket.

The justices are actually explaining more.

Much of the commentary on the interim relief docket has faulted the justices for failing to explain their reasoning in such decisions. But, in fact, they have provided more explanations over time. From 2015-17, the court engaged in a period of complete silence, with no written opinions for those years. This was emergency relief in its purest “shadow docket” form – swift, silent intervention. Thus, Will Baude and Steve Vladeck were on to something when they first began calling attention to the court’s reliance on such unsigned, unexplained emergency orders.

A modest shift began in the 2018-19 term, when written opinion rates reached 10%. This was followed by 13.5% in the 2019-20 term before dropping back to around 8% in the 2020-21 term. Then came a dramatic increase in the 2022-23 term, when written opinion rates jumped to 28%. And, despite the rhetoric otherwise, they have remained elevated, at 23.1% in the 2023-24 term and 27.9% in the period studied.

This transformation is most dramatic for granted applications. From 2014-2021, only 11.6% of emergency grants included written explanations – the court simply said “yes” and moved on. Since 2022, however, 39.5% of granted applications have received written opinions. Even denials of applications are explained far more often than in the past, jumping from 5.5% (2014-2021) to 19.5% (2022-2024).

Two possible explanations for this come to mind. First, the justices may be responding to sustained criticism of the secrecy of the “shadow docket.” Indeed, the justices themselves have made clear they are aware of this criticism: Justice Samuel Alito has defended the court against media portrayals of the shadow docket as “sinister,” and Kagan has expressly suggested that the court should explain its reasoning in such cases.

A second explanation may be that the court (at least outside of the death penalty context) is now handling weightier cases that require explanation. For example, the shift towards separation of powers disputes may require more justification – given the enormous stakes at issue, silence becomes harder to defend.

The bottom line

The interim relief docket continues to be a pivotal part of the court’s workload. Most commentators have concentrated on the court’s lack of explanations and its alleged ideological bias in emergency decisions. By analyzing the interim relief docket in depth, some of this narrative is borne out, and some is not.

First of all, the reality is more complex than simple ideological bias. Overall case outcomes appear balanced (52.5% liberal, 47.5% conservative), but when the court chooses to grant relief, 75% of those grants produce conservative outcomes. This pattern has persisted regardless of which party controls the White House. This shows a court that does not necessarily favor one side in all emergency decisions, but does reveal one that grants emergency relief selectively in cases that advance conservative legal positions.

Commentators have also focused on the supposed lack of explanations in emergency decisions. But the frequency of these has actually increased dramatically since 2022. We also see an unprecedented amount of public disagreement among the justices, with 67% of substantive applications producing dissents or disagreement statements, more than double the recent averages.

One of the bigger questions going forward is whether this pattern of selective grant rates and increased public disagreements represents the interim relief docket’s new normal, or whether we’re simply witnessing the beginning of the interim relief docket’s next era.

The post What the emergency docket actually looks like appeared first on SCOTUSblog.