If you’re tired of censorship and dystopian threats against civil liberties, subscribe to Reclaim The Net.

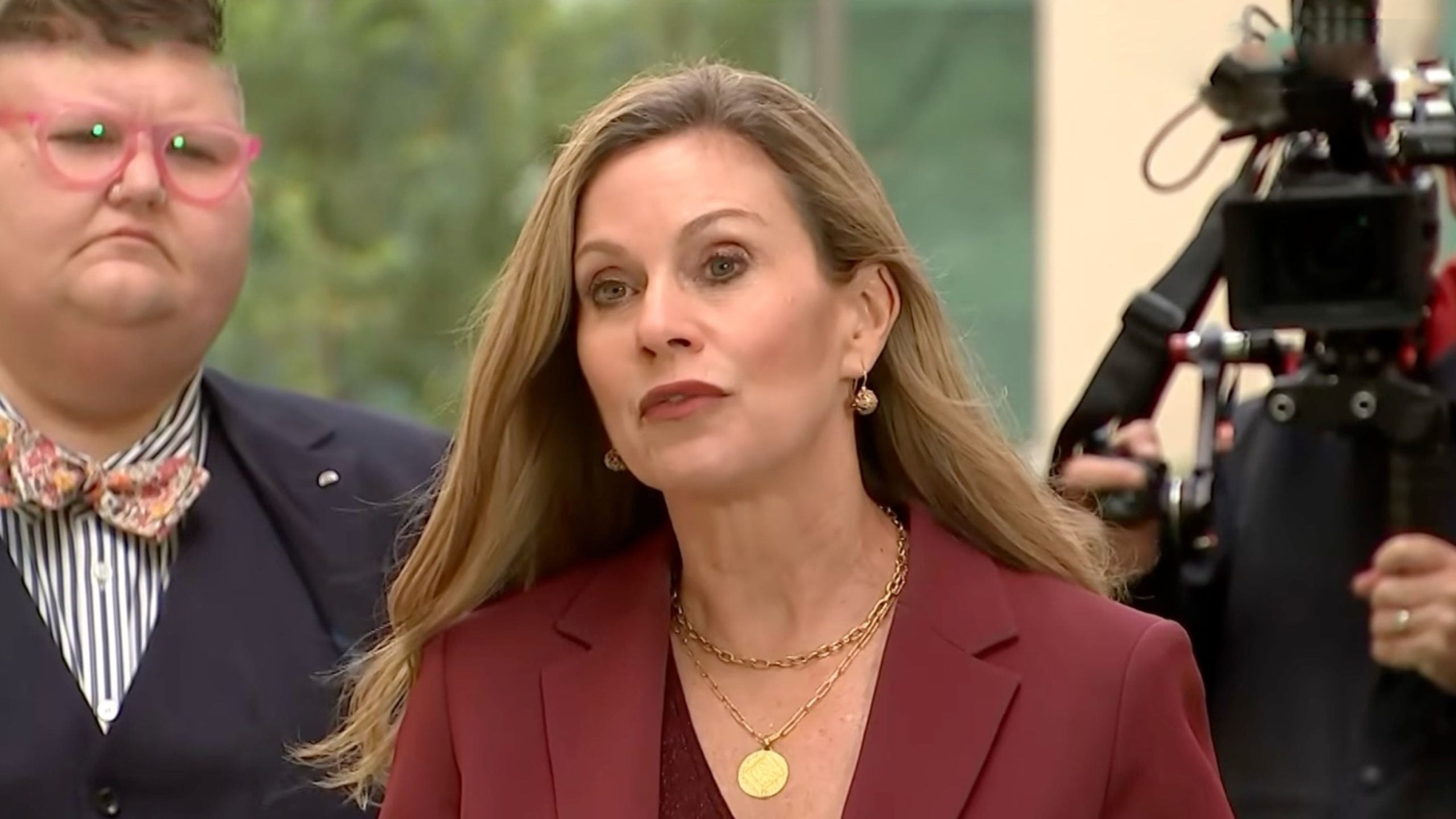

At a press conference that could have been a comedy sketch idea, Australia’s “eSafety” Commissioner Julie Inman Grant and Social Services Minister Tanya Plibersek stood before the cameras and solemnly warned the nation about the perils of surveillance. Not from government programs or sweeping digital mandates, but from smart cars and connected devices.

The irony was not lost on anyone paying attention.

Both Grant and Plibersek are enthusiastic backers of the country’s new online age verification law, the so-called Social Media Minimum Age Bill 2024, a law that has done more to expand digital surveillance than any gadget in a Toyota.

The legislation bans under-16s from social media and requires users to prove their age through “assurance” systems that often involve facial scans, ID uploads, and data analysis so invasive it would make a marketing executive blush.

But on the same day she cautioned the public about the dangers of “connected” cars sharing sensitive information with third parties, Grant’s agency was publishing rules that literally require social media platforms to share sensitive data with third parties.

During the press conference, Grant complained that “it’s disappointing” YouTube and other platforms hadn’t yet released their guidance on how they’ll implement verification.

She announced that eSafety will begin issuing “gathering information notices” on December 10, demanding details from companies about how they plan to comply once her expanded powers take effect.

She also warned that some of the smaller apps users are migrating to may soon “become age-restricted social media platforms.”

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) explains that compliance under this law can involve “age estimation” using facial analysis, “age inference” through data modeling of user activity, or “age verification” with government ID.

All three options amount to building a surveillance apparatus around everyday users. Facial recognition, voice modeling, behavioral tracking; pick your poison.

Most platforms outsource this work to private firms, which means that the same sensitive data the law claims to protect is immediately handed to a commercial intermediary.

Meta, for example, relies on Yoti, a third-party ID verification company. Others use firms like Au10tix, which famously left troves of ID scans exposed online for over a year.

The law includes what politicians like to call “strong privacy safeguards.” Platforms must only collect the data necessary for verification, must destroy it once it’s used, and must never reuse it for other purposes.

It’s the same promise every company makes before it gets hacked or “inadvertently” leaks user data.

Even small dating apps that claimed to delete verification selfies “immediately after completion” managed to leak those same selfies. In every case, the breach followed the same pattern: grand assurances, then exposure.

Julie Inman Grant calls it protecting the public. Tanya Plibersek calls it social responsibility. The rest of us might call it what it actually is: institutionalized data collection, dressed in the language of child safety.

If you’re tired of censorship and dystopian threats against civil liberties, subscribe to Reclaim The Net.

The post Australia’s Top Censor Warns of Surveillance While Hypocritically Expanding It appeared first on Reclaim The Net.