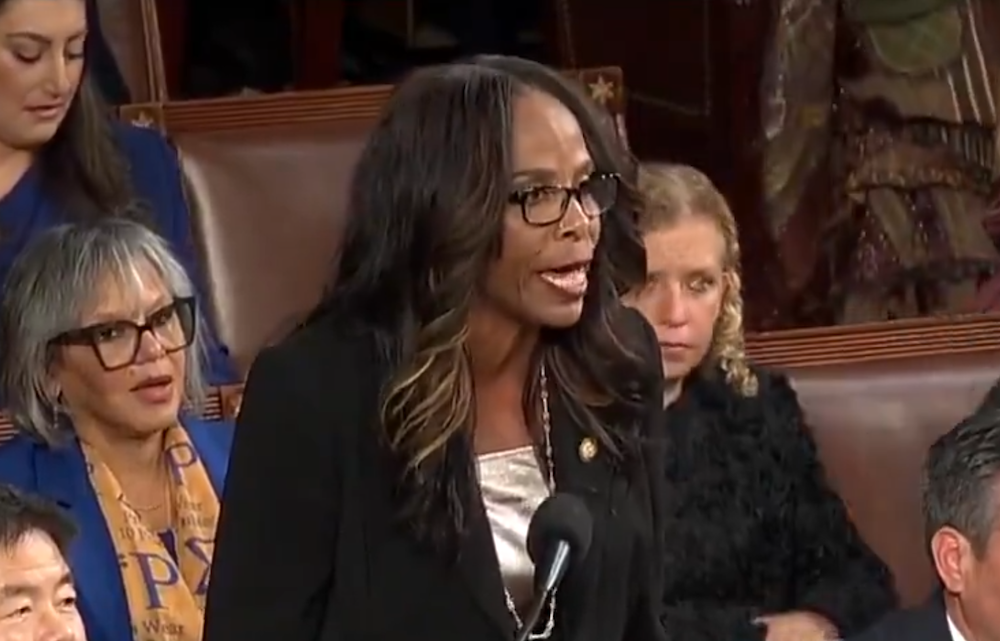

The opening session of the 119th Congress kicked off with drama as Democrat Delegate Stacey Plaskett from the U.S. Virgin Islands derailed proceedings during the Speaker election. Plaskett, who does not hold voting power in Congress, took to the microphone in an outburst that drew gasps from lawmakers and left House Parliamentarian Jason Smith clarifying basic procedural rules.

Plaskett’s grievances centered on the non-voting status of delegates representing U.S. territories such as the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and Guam, as well as the District of Columbia. Together, these jurisdictions account for nearly four million residents who lack voting representation in the House. However, Plaskett’s impassioned approach quickly veered into a heated confrontation with House leadership.

“Mr. Speaker, I ask why the names of the delegates and resident commissioners were not called,” Plaskett demanded, interrupting the clerk’s reading of the roll. Her frustration culminated in an insistence that Smith publicly recite the rules that bar territorial delegates from voting in the Speaker election.

House Parliamentarian Smith calmly explained the procedure, citing Section 36, which stipulates that only representatives-elect from states are qualified to vote in the election of a Speaker. Despite the explanation, Plaskett persisted, saying, “ What was supposed to be temporary has now effectively become permanent. We must do something about this problem.” Though she decried the U.S. territories’ lack of voting rights, she failed to address why these issues have remained unresolved during decades of Democrat-led administrations.

WATCH:

The United States has five main inhabited territories—Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands—along with the District of Columbia, which is a federal district rather than a state. While residents of these areas are U.S. citizens (with the exception of American Samoa, where they are U.S. nationals), they lack full voting representation in Congress. Each territory and D.C. send non-voting delegates or a resident commissioner to the House of Representatives. These representatives can debate legislation, introduce bills, and serve on committees, but they are not allowed to vote on final passage of legislation or participate in crucial votes, such as the election of the Speaker of the House.

The Constitution guarantees voting representation in Congress to states, and because territories and D.C. are not states, they fall outside this framework. The roles of their non-voting representatives are granted through federal laws rather than constitutional authority. Historically, territories were viewed as temporary holdings, expected to either achieve statehood or gain independence. However, many of these territories have remained under U.S. control for over a century. The District of Columbia was deliberately created as a neutral federal district without state-like powers.

Territories and D.C. collectively represent over four million people, many of whom serve in the U.S. military at disproportionately high rates and contribute to the economy through tourism, agriculture, and other industries. Despite this, territorial residents do not pay federal income taxes—although they pay other forms of taxes—and receive federal funding. This unique arrangement is often cited as a reason for their limited voting rights, alongside the lack of statehood. Efforts to change this dynamic, such as Puerto Rico’s referendums on statehood or D.C.’s statehood advocacy, have gained traction but face considerable political resistance. Opponents often argue that granting statehood to these areas would disrupt the balance of power in Congress, as most territories and D.C. lean Democratic.

(FREE GUIDE: Trump’s Secret New “IRS Loophole” Has Democrats Panicking)